Geospatial Sovereignty: Why it requires both Law and Architecture

In my recent post on an architecture for geospatial sovereignty, I argued that “sovereign” in the age of AI can’t mean “isolated.” It has to mean choice: the ability to adopt best-in-class technology while avoiding lock-in to a single vendor, technical standard, or jurisdiction. That requires a modern, layered architecture — open formats, modular compute, and an AI layer you can swap, configure, and govern.

But architecture and infrastructure are only half the story.

Geospatial data is uniquely sensitive: it’s precise, persistent, and increasingly predictive. Once you add AI models and systems that generate insights (and sometimes decisions), the question of sovereignty quickly becomes an alignment problem across technology, operations, and law. You can build a stack that can be sovereign, but without enforceable rights, controls, and accountability, sovereignty stays aspirational.

That’s why I invited Kevin Pomfret, Partner at Pierson Ferdinand, and an expert in the convergence of data, technology, and governance, to write this guest post. Kevin lays out a practical framework and playbook for thinking about sovereignty across the same layers we use in architecture— data, compute, and AI— then maps those layers to the contractual, regulatory, and operational obligations that make sovereignty real in production systems.

If you’re designing Agentic or GeoAI systems for critical infrastructure, government, regulated industries, or any organization dealing with sensitive Location Intelligence, this piece is a strong companion to the architectural view— and a reminder that the “sovereign stack” must be matched by sovereign governance.

In governments, multinational organizations, and private enterprises around the world, digital sovereignty has moved from an abstract political aspiration to a concrete operational requirement. According to the World Economic Forum, digital sovereignty, cyber sovereignty, technological sovereignty and data sovereignty refer to the ability to have control over your own digital destiny – the data, hardware and software that you rely on and create.

As AI-enabled systems increasingly direct supply chains, transportation networks, emergency response, and other mission-critical functions, sovereignty is no longer only an optimization challenge.

Technology alone cannot deliver it.

A nation or organization may invest in sovereign clouds, adopt open formats, or diversify its analytics stack— but these steps remain incomplete unless they are supported by a governance framework aligned with legal and policy requirements.

This is particularly true for geospatial information, which uniquely combines sensitivity, precision, persistence, and predictive value. Digital sovereignty is ultimately an alignment challenge: technical architecture, legal obligations, operational oversight, and institutional accountability must reinforce one another.

When one layer is weak, sovereignty becomes aspirational.

In the following sections, I’ll explain how a layered geospatial architecture— paired with a correspondingly layered governance framework and playbook — strengthens digital sovereignty, especially as organizations confront rising expectations around privacy, intellectual property, national-security safeguards, and responsible AI.

Recent thinking on geospatial sovereignty emphasizes that modern sovereignty does not require digital isolation or rigid localism. Instead, it requires freedom of choice: the ability to adopt best-in-class tools without becoming dependent on a single provider, jurisdiction, or technical standard.

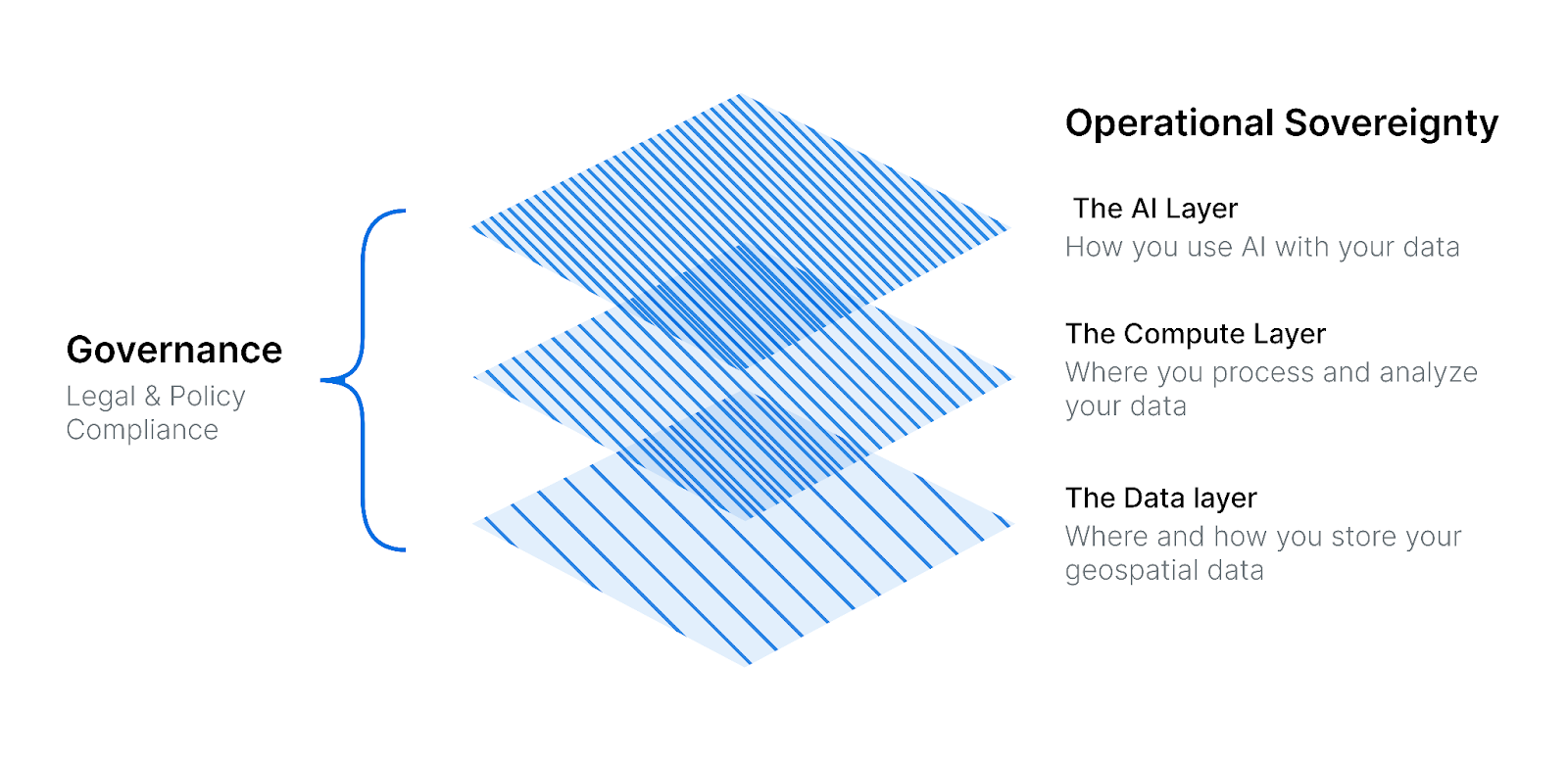

This flexibility emerges from a layered architectural model of the whole data system:

Adopting open table formats and interoperable standards allows organizations to maintain data portability even as storage or compute environments change. Moving away from proprietary silos enables a more sovereign data posture where ownership and control remain with the organization—not the vendor.

Separating storage from compute increases resilience. Analytics can occur in different environments (on-premises, sovereign clouds, or commercial clouds) without disrupting access to geospatial information. Compute becomes modular and substitutable.

As organizations transition toward agentic geospatial systems— where users interact conversationally with AI models that generate maps, analyses, and workflows— they must retain the ability to configure, train, and switch among AI providers. Sovereignty is undermined when an AI system becomes indispensable but opaque.

These layers provide the technical capacity for sovereignty. But capacity alone is insufficient. Technical openness may create optionality, but governance establishes enforceability, accountability, and legal legitimacy.

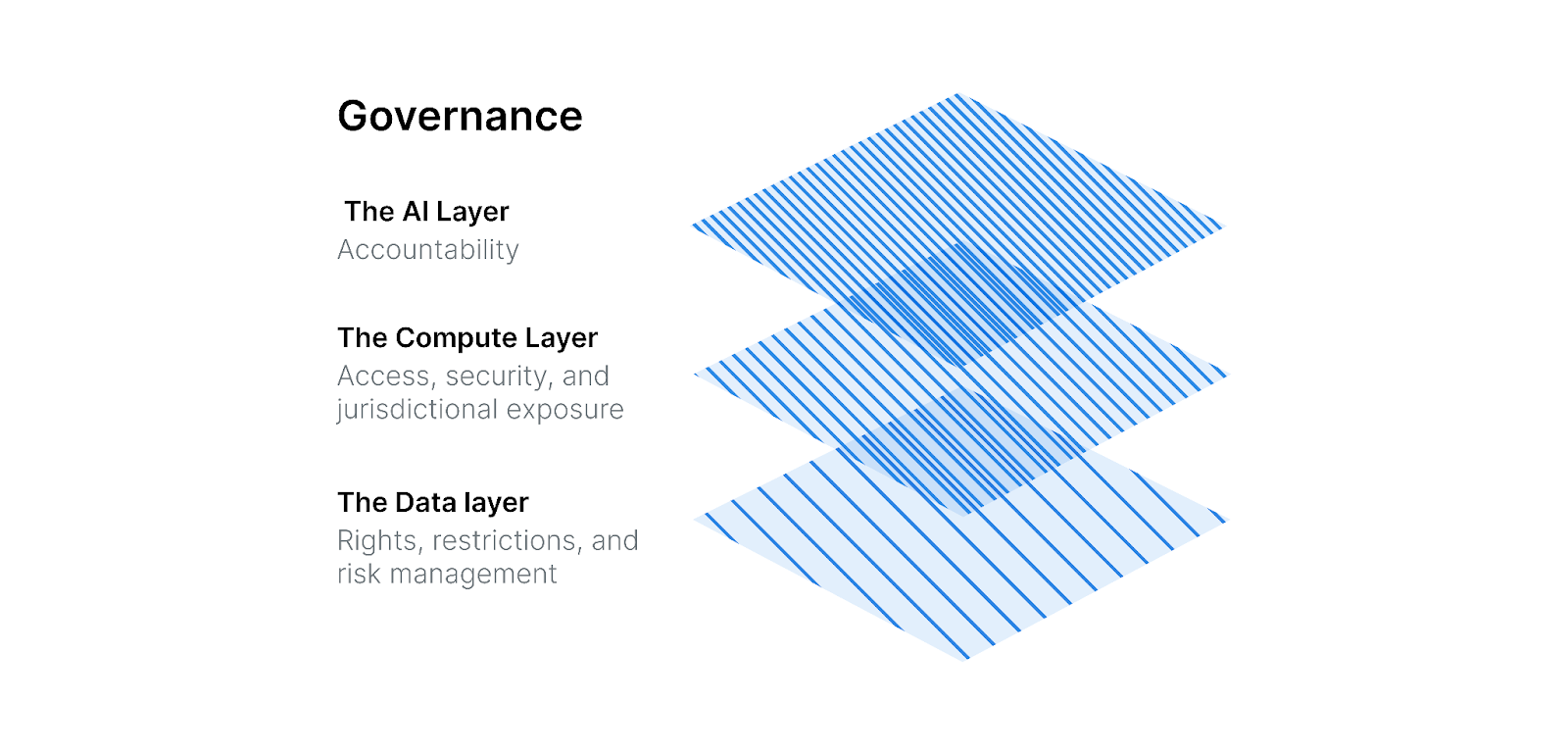

For geospatial organizations, it is helpful to consider governance across the same three layers. Data, compute, and AI each present distinct legal and operational risks.

At the data layer, sovereignty hinges on ensuring an organization actually holds the rights required to use, combine, train, analyze, distribute, or transfer geospatial information.

Because geospatial datasets often derive from numerous sources (satellites, sensors, vendors, public bodies, and crowdsourced contributors), organizations must conduct rigorous rights validation, due diligence, and intake review. This includes:

- Confirming the scope of permitted uses, including whether training, model fine-tuning, or derivative outputs are allowed

- Ensuring attribution, confidentiality, and retention obligations can be operationalized

- Identifying geographic, temporal, or functional restrictions embedded in contracts

- Reviewing whether data can cross borders, be co-mingled with other datasets, or be used in commercial applications

- Evaluating restrictions on sensitive locations, critical infrastructure, or defense-related imagery

Failure to validate these rights exposes organizations to breach-of-contract claims, misuse of confidential information, misappropriation of proprietary data, or violations of privacy or national-security regulations.

As data becomes the substrate for AI training, modeling and decision-making, these risks multiply. Governance at the data layer establishes the baseline legality and defensibility of all downstream AI activities.

Where data is processed—and, as importantly, who can access it—matters almost as much as the data itself. Organizations increasingly rely on third-party compute environments, remote administrative support, and distributed processing pipelines, all of which create jurisdictional and security implications.

Key questions at this layer include:

- Who controls the infrastructure and metadata?

- Where are logs, backups, and failover instances stored?

- Do administrators or subcontractors have visibility into sensitive content?

- What safeguards prevent unauthorized or extraterritorial access?

- Do support activities inadvertently create cross-border transfers?

- Can government authorities compel access to systems, keys, or stored data?

Governance must ensure alignment between vendor and customer contractual commitments, technical controls, and regulatory obligations. In practice, many organizations do not invest enough in due diligence to confirm that vendor promises (such as data residency or access controls) are accurate. Nor do they have sufficient audit rights—or the practical capability— to verify that environments remain as represented over time.

For geospatial organizations, whose systems often contain sensitive location-based intelligence, a disconnect between contract and capability can undermine compliance and erode trust.

The AI layer presents the most rapidly evolving and complex governance landscape. As geospatial organizations integrate predictive models, automated mapping, and agentic workflows, they must confront business, contractual, and regulatory risks associated with:

- Model transparency, interpretability, and explainability

- Data quality, representativeness, and geographic bias

- Spatial or temporal drift

- Over-reliance on automated decision-making

- Inaccurate or harmful outputs

- Reuse of generated content beyond intended scope

- Lack of provenance or auditability in training data and model lineage

Regulators and customers increasingly expect organizations to demonstrate clear governance structures: documented risk assessments, oversight mechanisms, human-in-the-loop controls, and traceable model management practices.

The stakes are high for applications such as land-use decisions, infrastructure design, transportation planning, emergency management, financial risk assessments, insurance claims, and even national-security operations. Errors or biases can produce material, real-world consequences. AI governance must ensure models are not merely high-performing— they must be defensible, accountable, and aligned with organizational obligations and public expectations.

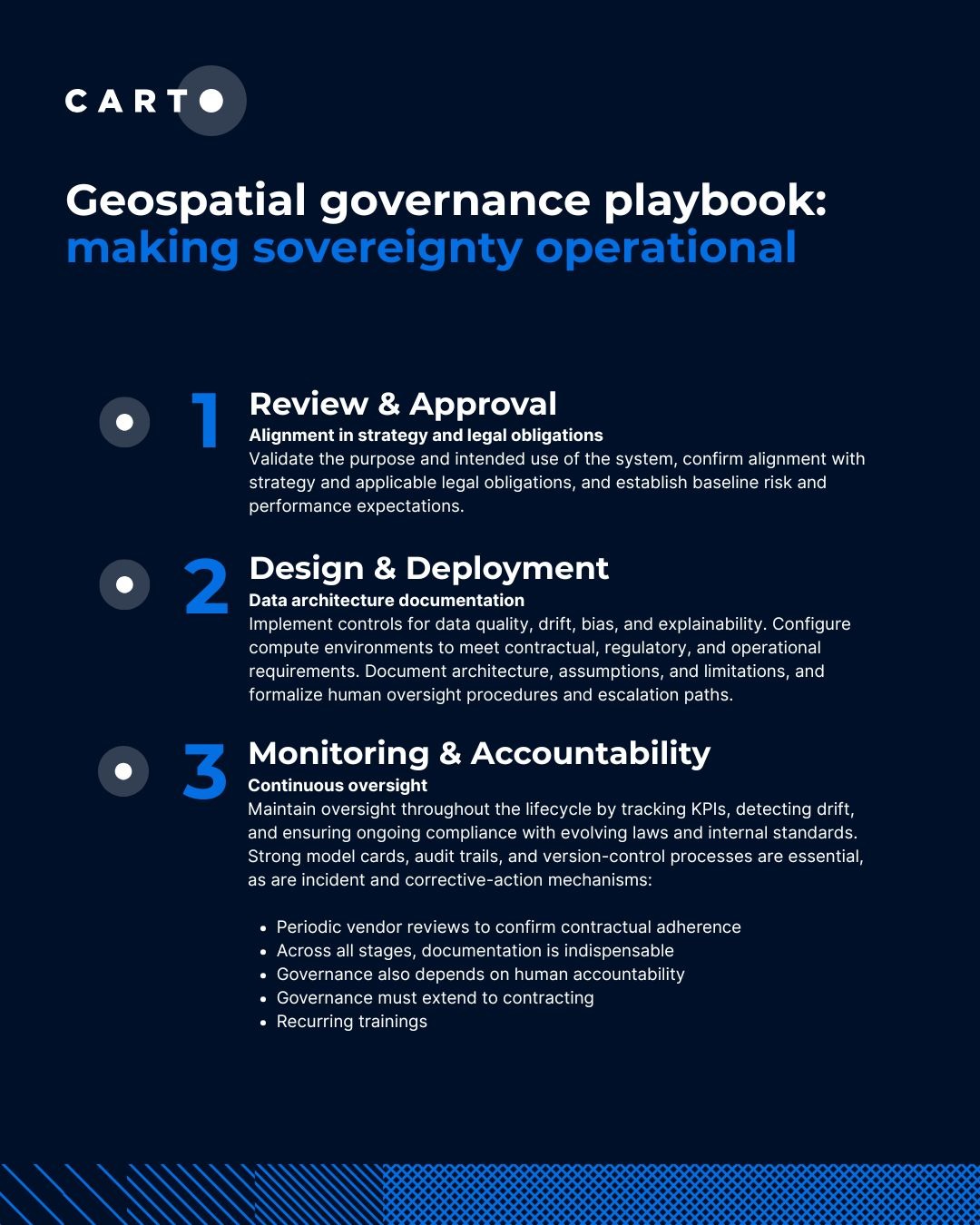

Technical safeguards and legal considerations translate into sovereignty only when integrated into a structured governance program. For geospatial organizations, this requires a lifecycle-based governance model that mirrors how systems are conceived, developed, deployed, and maintained.

A robust governance framework includes:

Validate the purpose and intended use of the system, confirm alignment with strategy and applicable legal obligations, and establish baseline risk and performance expectations. This includes confirming data rights and provenance, and assessing privacy, security, and national-security implications.

Implement controls for data quality, drift, bias, and explainability. Configure compute environments to meet contractual, regulatory, and operational requirements. Document architecture, assumptions, and limitations, and formalize human oversight procedures and escalation paths.

Maintain oversight throughout the lifecycle by tracking KPIs, detecting drift, and ensuring ongoing compliance with evolving laws and internal standards. Strong model cards, audit trails, and version-control processes are essential, as are incident and corrective-action mechanisms. This stage also includes periodic vendor reviews to confirm contractual adherence as systems evolve.

Across all stages, documentation is indispensable. Regulators, customers, and procurement teams increasingly expect evidence of responsible development, rigorous oversight, and transparent governance. Strong documentation strengthens defensibility in disputes, audits, and evaluations.

Governance also depends on human accountability. Assigning an AI sponsor or governance lead ensures policies are institutionalized and updated over time rather than treated as a one-off compliance exercise. Employee training should reflect AI roles and responsibilities.

Finally, governance must extend to contracting. Modern geospatial workflows involve intricate relationships among data providers, cloud vendors, model developers, and downstream customers. Contract terms govern ownership of inputs and outputs, permitted uses, liability allocation, training rights, redistribution, and compliance obligations—and often define the practical boundaries of sovereignty as much as the technical system.

Geospatial data sovereignty is not solely a technical mandate. It is a legal, operational, and institutional challenge that an organization must actively construct and maintain. Technical architectures provide resilience and flexibility, but governance provides legitimacy, accountability, and enforceability.

And sovereignty is not a static achievement. It is a continuous process— staying in step with changes to architecture, vendors, and contractual and legal obligations.