Map of the Month: Coffee Supply Chain Traceability

While some may view coffee as a commodity others celebrate its variety and the attributes that make each coffee unique. "Tracing" a coffee back to its source means not only identifying where it was grown and processed but also understanding the social environmental and economic conditions in those places. It goes beyond answering the questions "where did this coffee come from" and "who did what to get it here". Full traceability means knowing what is happening in those places and which parts of that story are relevant to where the coffee is now.

Introduction & Context

In a previous blog post we showed that there are approximately 12.5 million smallholder coffee farms that contribute to your daily cup of coffee. 44% of these farmers live below the poverty line and in order to address this poverty we need to acknowledge that the coffee supply chain is long and complex. This is particularly apparent as the coffee in your cup rarely comes from a single farm but in most cases from a blend of farms and possibly from several regions and countries as well. As you read through this post we encourage you to challenge and critically assess the need and value of traceability for both consumers and smallholder farmers.

Using traceability to understand quality and taste profiles

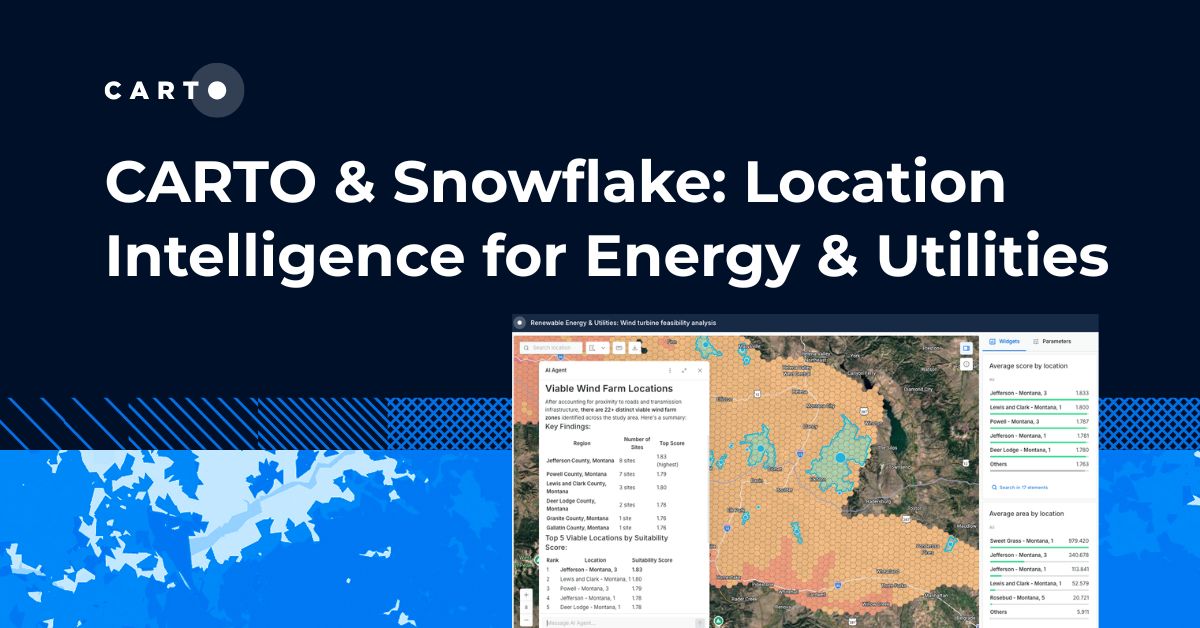

Certain regions and varieties are renowned and rewarded for their unique qualities. Let us take Ethiopia as an example - consumers of specialty coffee may be aware of the famous coffee region "Yirgacheffe" which has a reputation for excellence and a distinct flavor profile. Like wine this flavor profile is influenced by farmers’ choices such as which variety of coffee to grow and how to process the coffee once it’s picked from the tree as well as the terroir natural attributes including soil climate and altitude.

While the name "Yirgacheffe" is indeed the name of a town in Ethiopia most coffee that is traded as "Yirgacheffe" comes from a larger catchment area. Over the last decade Ethiopia has changed its internal system for classifying coffees based on where they come from how they taste and other attributes. The classification system is complex. Administrative borders have changed. An internal trading platform - the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange - established aggregation and warehousing hubs for coffees of similar provenance throughout the country. These different systems can make it difficult to trace a coffee beyond the name "Yirgacheffe".

Using CARTO Enveritas was able to display a current visualisation of the complexity of these types based upon the ECX classification system.

Defining and evaluating the concept of traceability

Above we highlight the example of Ethiopia and the role that geographic traceability can play in associating coffees with places.

However we cannot assume that just because a supply chain is traceable that it is also a responsible or ethical supply chain. If traceability is important to you as a consumer we challenge you to add a similar value to traceability of the sustainability issues in the supply chain. Coffee beans are touched by many hands before they make it to your cup even before they leave their own community of origin. Rarely can it be assumed that all the coffee a farmer produces passes through the same chain of custody.

This map shows that most farmers are not represented by organised groups such as co-operatives. Instead they sell to a variety of different coffee aggregators. Even if it is possible to physically trace a coffee to a farmer group or a co-operative these buyers need to maintain member support systems and physically separate out non-member coffees in order to uphold traceability requirements.

Physical traceability is a tool in a responsible coffee buyer’s toolbelt but it can’t be the only one. It needs to be complimented by verification of the sustainability issues and a system in which we are incentivised to highlight and solve those issues.

The issues themselves are real and deserve attention. Over 5 million coffee farmers live in poverty and the challenges of making coffee more sustainable cannot fall solely on their shoulders. We need to support them on this journey and to do so we need to understand the issues they face and the trade-offs they consider in adopting different practices. In Yirgacheffe for example farms are exceedingly small trees are aging and productivity is inconsistent. Farmers and buyers both want these issues to get better.

Such information is possible to gather using technology and boots-on-the-ground and above all by challenging the current systems that do not reward surfacing these issues. The coffee industry needs to be held to a higher standard across the reliability of the data on the issues themselves and the way that information is presented to consumers - so they are under no illusion that a label indicating an origin means that the farmers in that origin are thriving and prosperous.

Want to get started?

.png)

.png)